What Removing Tumors Taught Me About Justice

As a pediatric surgeon and scientist, I spend my days navigating one of medicine's most delicate paradoxes: how to remove diseases such as tumors and harmful tissues without harming the patient. When I operate on cancers, especially in small children, every operation requires me to distinguish cancer from healthy tissue, to remove what threatens life while preserving what sustains it. The margin between cure and catastrophe is often measured in a tenth of a millimeter.

Watching the recent escalation of immigration enforcement in America, I cannot help but see the same paradox playing out on a societal scale, but with far graver consequences.

The comparison between cancer and crime is not new. People have long used the language of malignancy to describe criminal behavior: we speak of crime as "cancers spreading" through neighborhoods, of "invading" communities, of the need to "excise" bad actors before they metastasize. But if we take this metaphor seriously, we must also take seriously what surgery has learned over centuries of cutting into human bodies: aggression without knowledge and precision kills.

The Cancer We Choose to See

We can define cancer as cells that, though originating from the body itself, grow uncontrollably, consume resources meant for healthy tissue, and ultimately threaten the body's survival. The definition is clinical, but the reality is far more complex. Not every abnormally growing cell is cancer. Not every tumor requires surgery. And the decision to operate, to physically excise tissue from a living person, is never taken lightly.

Now, let's consider what constitutes "criminal behavior" in our current enforcement regime. Yes, violent or sexual offenders who harm others represent a genuine threat, much like aggressive malignancies. But our dragnet has widened to capture people guilty of minor traffic violations, DUI, trespassing, marijuana offenses, shoplifting, or simply protesting the aggression of law enforcement. It is as if we've expanded the definition of "cancer" to include inflamed tissue, benign growths, and cells that are merely different from their neighbors.

This is not a semantic distinction. Just as many tissues in our bodies exist in temporarily abnormal states (inflamed, infected, or healing), many people in our society commit minor violations without posing existential threats to the social fabric. As a society, we do not like it, but we accept that pursuing punishment that doesn't fit the crime is worse. We even do that for people who run our government, some Congress members and the current president, who have also committed and been convicted of crimes. A surgeon who treated every infected limb as if it were stage-four cancer would leave a trail of unnecessary suffering. A society that treats every misdemeanor or nuisance as an emergency requiring immediate extraction does the same.

When Surgeons Become Butchers

The history of medicine is littered with cautionary tales about what happens when practitioners lose sight of this balance. Perhaps no case illustrates this more starkly than that of Christopher Duntsch, the neurosurgeon known as "Dr. Death."

Between 2011 and 2013, Duntsch operated on 38 patients in Texas. Of those, 33 were left seriously injured, and two died on the operating table. He severed nerve roots, left sponges inside spinal cavities, removed parts of vertebrae that should have remained, and operated on entirely wrong levels of the spine. Colleagues who observed his work described it as "criminally negligent," yet he continued operating for nearly two years before his medical license was finally revoked. Yet, after that, he was able to continue working at another hospital.

Duntsch wasn't trying to harm his patients, at least not consciously. He believed he was removing tumors, fixing injuries, and alleviating pain. But he lacked the fundamental requirements of his role: adequate training, careful judgment, respect for anatomy, and above all, the humility to recognize the limits of his abilities. Reportedly under the influence of drugs, his aggressive confidence in cutting, combined with his inability to distinguish what should be removed from what should be preserved, transformed an operating room into a chamber of horrors.

The parallel to overly aggressive law enforcement is uncomfortable but unavoidable. When agents raid homes before dawn, separate parents from children, detain citizens based on appearance or accent, and sweep up bystanders in their pursuit of designated targets, they are practicing the Christopher Duntsch school of social surgery. They may believe they are protecting the community and society, but without precision, training, and respect for the "normal tissue" of ordinary people living ordinary lives, they inflict wounds that won't heal. The deaths of Renee Good and Alex Pretti dominated headlines, yet they represent only the most visible casualties in a broader trail of destruction.

The Lessons of Radical Mastectomy

The medical profession's reckoning with overly aggressive surgery didn't begin with Dr. Death. For much of the late 19th century until the 1970s, breast cancer treatment was dominated by the radical mastectomy, a procedure developed by William Halsted, who is still considered the father of modern surgery, that was first described in 1882. Halsted's operation removed not just the breast but also the underlying chest muscles, the entire system of lymph nodes under the armpit, and often additional tissue. Women emerged from surgery disfigured, their arms permanently swollen, their range of motion destroyed.

Halsted justified this mutilation by arguing that only the complete removal of all tissues and areas where the cancer could spread would save lives. He was right that lives were saved. However, he was wrong that aggressive removal was necessary. Studies eventually showed that radical mastectomy offered no survival advantage over less invasive procedures. The unnecessary suffering inflicted on thousands of women stemmed not from malice but from a flawed premise: that more aggressive means more effective.

It took decades for the medical establishment to challenge Halsted's orthodoxy. Surgeons who questioned the radical mastectomy were accused of endangering patients, of not taking cancer seriously enough. But the data eventually spoke for itself. Today's breast cancer surgery is far more conservative, guided by precise imaging, molecular markers, and an understanding that preserving quality of life is as important as extending its duration.

The transformation required courage from surgeons willing to question authority, researchers willing to conduct studies that might prove their mentors wrong, and institutions willing to change course despite decades of precedent. It also required something harder to quantify: a shift from viewing the patient as a battlefield where cancer must be defeated at any cost, to seeing them as a whole person whose treatment must balance multiple, sometimes competing, values.

The Context We Cannot Ignore

When we discuss law enforcement in America, we cannot separate the conversation from the specific history of who gets treated as cancer and who gets treated as healthy tissue. The killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin in May 2020 catalyzed one of the largest protest movements in American history, not because it was an isolated incident, but because it represented a pattern so pervasive that millions of people recognized it immediately.

Floyd, like Eric Garner before him, like Breonna Taylor, like Philando Castile, like countless others, was killed during an interaction that began with suspicion of a minor offense. A counterfeit twenty-dollar bill. Selling loose cigarettes. Sleeping in one's own home. A broken taillight. In each case, officers approached these encounters with the presumption that aggressive intervention was necessary and that the person before them posed a threat requiring immediate control.

This is the enforcement equivalent of Halsted's radical mastectomy, an approach that assumes maximum intervention is always justified, that collateral damage is acceptable, that the target's humanity is less important than the officer's authority. And like the radical mastectomy, it might work on the surface, but there are severe long-term damages, and overall quality of life might not improve. Communities subjected to aggressive policing might seem quieter on the surface, but they don't become safer; they become more traumatized, more distrustful, more fractured.

The Black Lives Matter movement emerged as a direct response to this pattern of treating certain bodies as inherently suspicious, inherently dangerous, and inherently disposable. The movement called for better police training in the appropriate use of force, accountability for misconduct, and investment in community resources rather than enforcement. These mirror the medical profession's eventual recognition that healing requires more than just cutting.

The Technique of Precision

In the operating room, I teach my residents that one of the most important aspects of surgery is touch. How you hold the tissue matters. How you separate tumor from nerve, cancer from vessel, disease from health makes a difference. These technical skills require years of practice and constant mindfulness. A surgeon who rips through tissue, who uses force instead of finesse, who prioritizes speed over care, leaves behind damage that may never heal.

The same is true in law enforcement. When police departments invest in de-escalation training, when officers take time to investigate before acting, when arrests are conducted with attention to minimizing trauma not just to the target but to witnesses, family members, and the broader community, this is the law enforcement equivalent of surgical technique.

I've watched body camera footage of police approaching a situation with care, speaking calmly, taking time to assess, and using the minimum force necessary. I've also watched footage of officers approaching situations similar to this, as if everyone present were an enemy, as if any delay in exerting control represented weakness, as if the goal were domination rather than resolution. The outcomes are predictably different.

Consider a hostage situation, which actually illuminates the fallacy of overly aggressive enforcement. When a bank robber takes hostages, trained negotiators don't simply storm in shooting. They understand that the hostages are "normal tissue," innocent people whose safety is of the utmost importance. They understand that the robber himself, though dangerous, is also a human being whose death should be avoided if possible. The goal is to resolve the situation with minimum harm to everyone involved, even when that requires patience, creativity, and acceptance that the solution might not be the most emotionally satisfying one.

Although immigration enforcement has been rough and crude, in the current surge, the government seems to have abandoned any pretension of a careful approach. Agents raid workplaces, schools, churches, and homes, detaining not just their targets but anyone who happens to look suspicious, even children as young as five years old. They separate parents from children with no plan for reunification. They hold people in detention facilities for months while their cases are processed. This is not precision surgery; this is blunt force trauma.

The Rationalization of Harm

Perhaps the most dangerous aspect of overly aggressive enforcement is how easily it can be rationalized. Halsted and many surgeons who followed his teaching genuinely believed that radical mastectomies were saving lives. Christopher Duntsch apparently believed he was an exceptional surgeon, as he often boasted to other surgeons. The doctors who sterilized tens of thousands of people deemed "unfit" in the early 20th century believed they were protecting society from contamination.

Medical history teaches us that good intentions, or even good short-term outcomes, don't prevent bad long-term consequences. What matters is conscience, humility, logic, and the willingness to acknowledge when people are suffering.

Current aggressive immigration enforcement operates under the rationalization that removing all "criminal elements" (a category now expanded to include people whose only violation is lacking proper documentation) will make America safer and more prosperous. This logic ignores what we know about how communities actually function. People without legal status still contribute to their communities as workers, parents, neighbors, and friends. Tearing them out of the social fabric doesn't remove cancer; it removes tissues that look different. And by doing so, it also damages the surrounding normal tissue.

The data support this. Studies consistently show that immigrants, including those without legal status, commit crimes at lower rates than native-born citizens. The states and cities with the largest immigrant populations tend to have lower crime rates, not higher. The economic argument also fails: mass deportation would devastate industries from agriculture to construction to healthcare, while the cost of detention and removal runs into billions of dollars annually. This doesn't include the tremendous moral toll of tearing families and communities apart.

So why persist with an approach that the evidence suggests doesn't work? Partially because of the same factors that allowed Halsted's orthodoxy to persist for decades: institutional inertia, deference to authority, and the emotional appeal of "doing something" even when that something is counterproductive. But also because, as with much of American history, there's a question of whose bodies we consider expendable: women, minorities, the poor, the disabled, and immigrants.

The Multidisciplinary Imperative

Modern oncology has learned that surgery alone is rarely the answer. We now approach cancer with multidisciplinary teams that include surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists, radiologists, nurses, social workers, psychologists, and nutritionists. We understand that a patient's ability to fight cancer depends on their overall health, their mental state, their support system, and their economic resources.

Similarly, addressing crime and social disorder requires more than enforcement. People commit crimes for complex reasons: poverty, trauma, addiction, mental illness, lack of opportunity, and community breakdown. Addressing only the criminal act while ignoring these underlying causes is like removing a tumor while ignoring the patient's immune system, nutrition, and overall health. The cancer will come back.

This is not soft-headed idealism; it's pragmatic effectiveness. Recidivism rates drop dramatically when formerly incarcerated people receive education, job training, housing assistance, and mental health treatment. Communities become safer when they have strong schools, economic opportunities, mental health services, and social cohesion. These interventions are the societal equivalent of chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy, all the tools that work alongside, not instead of, carefully targeted enforcement.

The current approach of aggressive detention and deportation with no attention to the broader context of people's lives is like proposing to cure cancer through surgery alone while defunding research into radiation and immunotherapy. It's willfully ignorant of what we know works.

The Side Effects We Cannot Ignore

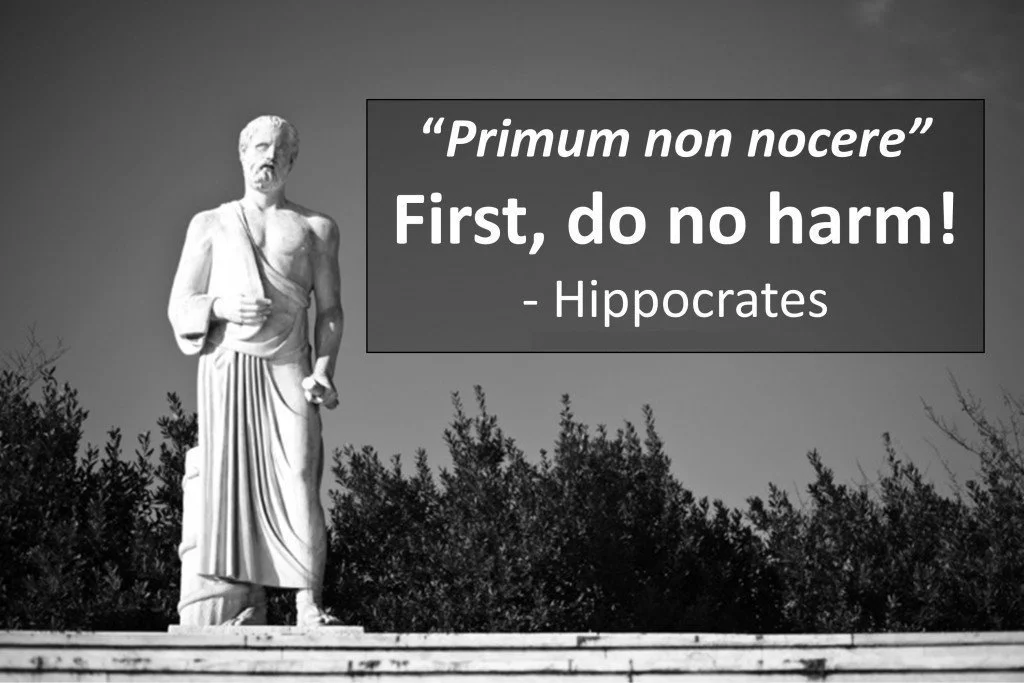

In medicine, we have a term for harm caused by treatment: iatrogenic injury. It refers to illness, disability, or death that results not from disease but from medical intervention itself. A surgeon who accidentally severs a nerve during tumor removal has caused iatrogenic injury. A medication that cures one condition while damaging the liver causes iatrogenic harm.

The principle of "first, do no harm" requires us to consider whether our interventions might cause more suffering than the disease itself. Sometimes the answer is that the cancer is so slow-growing, the patient so elderly, that surgery would be more dangerous than watchful waiting. Sometimes the tumor is so entangled with vital structures that attempting removal would be fatal.

What are the iatrogenic effects of aggressive immigration enforcement? Children separated from their parents develop attachment disorders and trauma that will affect them for life. Communities lose essential workers, disrupting local economies. Families are bankrupted by legal fees and lost income. People who witness raids in their neighborhoods develop hypervigilance and mistrust of any authority. Citizens who "look immigrant" are subjected to increased scrutiny and discrimination. The social fabric tears not just where the target was removed, but throughout the surrounding tissue as well.

These aren't hypothetical harms. Mental health professionals working with separated families describe symptoms of severe trauma. Economists document the economic damage to communities that lose significant portions of their workforce. Sociologists track the breakdown of trust between immigrant communities and institutions they depend on (schools, hospitals, police) when people fear that any interaction might lead to detention and deportation.

And like Duntsch's paralyzed patients, these harms are often permanent. A child who spends years separated from their parents cannot get that childhood back. A business that closes because its workforce was deported cannot simply reopen. Trust, once broken between a community and the state, may never fully heal.

A Surgeon's Humility

I've performed thousands of operations in my career. I've removed tumors from places that seemed impossible to reach and saved patients who were given no chance of survival. But I've also had cases where I opened the abdomen or chest and realized the cancer was too extensive, too entangled with vital structures, too advanced for surgery to help. In those moments, the hardest and most important thing I can do is close the incision and admit that cutting will do more harm than good.

This is the humility that surgery has taught me and that our current enforcement regime desperately needs. The humility to ask: Is this intervention actually helping? Am I qualified to make this judgment? What am I destroying in my attempt to heal? When should I step back and try a different approach?

These questions aren't signs of weakness. They're signs of wisdom earned through centuries of medical mistakes, of unnecessary suffering inflicted by well-intentioned practitioners who lacked the humility to question their own orthodoxies.

The answer isn't to abandon enforcement entirely, any more than the answer to Halsted's excesses was to stop treating breast cancer or performing surgery. The answer is better knowledge and precision. Better understanding of the forces behind migration. Careful identification of genuine threats. Minimally invasive interventions. Attention to collateral damage. Integration with other approaches, such as education, economic development, mental health care, community support, and global investment in the development of poor countries, and more. And above all, recognition that we're dealing with human beings embedded in complex social tissue, not isolated malignancies that can be simply cut out.

I took an oath on my first day as a medical student: first, do no harm. Law enforcement officers take an oath, too: to protect and serve. Both oaths require us to think carefully about who we're actually protecting, who we're actually serving, and whether our interventions heal or wound the body we've sworn to care for.

The operating room has taught me that healing is hard work. It requires training, skill, judgment, and constant self-examination. It requires the courage to admit when we're wrong and the humility to change course. Most of all, it requires us to see the person in front of us not as a problem to be solved or a threat to be eliminated, but as a human being worthy of care, precision, and respect.

That's not just good medicine. It's the foundation of a just society.